Bare Metal Programming on Raspberry Pi and QEMU

From a simple copy-paste to head-scratching dive through the binary.

Have you ever wondered how a computer executes the first program? I had this small, late-night curiosity on how to develop a working operating system for a specific machine, so I tried to make a very simple one.

Getting used to the environment

It would be unwise for me to have big ambitions for this. I don’t want to create a “Windows/Mac/Linux competitor”, I just want to see how the execution works. I looked up for a resource on how to create a “Hello world” program running on bare metal.

I chose Raspberry Pi as the platform because of the open source nature of some of its software, and it’s running on ARM, which they say it’s has a RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) architecture. For me, that sounds less intimidating than x86. I never directly worked on assembly codes from both ISAs, though.

OSDev Wiki

After some research I found this website: wiki.osdev.org. It provides resources for many kinds of machines/architectures. I am trying their tutorial on Raspberry Pi Bare Bones.

“Hello world” Kernel

The wiki provides a tutorial on how to write “Hello world” program on bare metal Raspberry Pi 2 Model B. I followed their steps which you can see on my repo raspi2b-osdev-wiki-example. The explanations there are quite good for introducing me to how things work, although I am yet far away from fully understanding each of them.

Running the kernel on QEMU

Running the kernel is simple. Using the produced .ELF file, we can run this command:

1

2

3

qemu-system-arm \

-M raspi2b \

-kernel out/img/kernel.elf

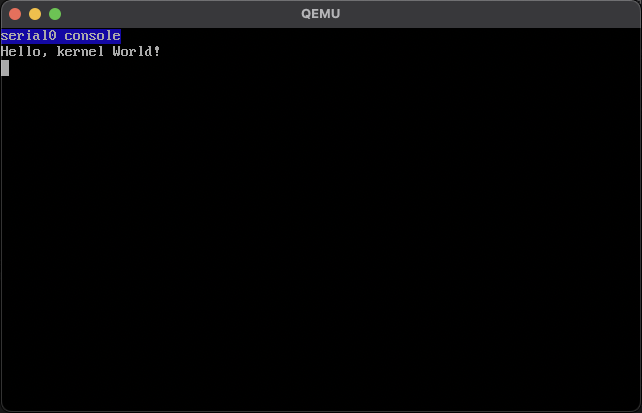

Then pick View -> serial0. You can see the Hello, kernel World! message there. You can also use -nographics mode and QEMU will automatically redirect serial output into stdio.

Serial console outputs correctly, yay!

Serial console outputs correctly, yay!

Problems with the kernel image?

I’m using QEMU version 9.0.2. Other versions may have different behaviors.

The OSDev Wiki mentioned aside from using the ELF, we can also boot up QEMU using the kernel image we just generated using objcopy. This image will eventually be used for the real hardware to boot up the operating system. However, when I ran:

1

2

3

qemu-system-arm \

-M raspi2b \

-kernel out/img/kernel7.img

There was no output. I wondered why. To me this was an opportunity to learn about binary analysis, so I tried to mess with the binary image and the ELF.

TL;DR: The solution was actually replacing

-kernel kernel7.imgwith-device loader,file=out/img/kernel7.img,addr=0x8000,cpu-num=0, as described in a related StackOverflow post. Following texts explain how did I conclude the problem was “wrong image load”. Note that I haven’t tested the image in the actual hardware, only QEMU.

How it boots the kernel

From OSDev Wiki entry on Raspberry Pi: Booting the kernel:

The bootcode handles the config.txt and cmdline.txt (or does start.elf read that?) and then runs start.elf. start.elf loads the kernel.img at 0x00008000, puts a few opcodes at 0x00000000 and the ATAGS at 0x00000100 and at last the ARM CPU is started. The CPU starts executing at 0x00000000, where it will initialize r0, r1 and r2 and jump to 0x00008000 where the kernel image starts.

Suspicious binary locations

I booted up QEMU using the kernel.elf (where it worked), and tried to peek on the system memory around address 0x8000:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

> qemu-system-arm \

-nographic \

-M raspi2b \

-kernel out/img/kernel.elf

Hello, kernel World!

QEMU 9.0.2 monitor - type 'help' for more information

# Dump 40 words (4 bytes), starting from 0x8000

(qemu) xp/40w 0x8000

0000000000008000: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008010: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008020: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008030: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008040: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008050: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008060: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008070: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008080: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008090: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

It was empty! Am I using it wrong? I fired up objdump to check out what was inside the ELF file, even though I am not quite sure how ELF structure works. It shows that the entry point _start (not to be confused with __start with double underscore in the linker.ld) is located at 0x10000, and the addresses before that contains only 0x00.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

> arm-none-eabi-objdump -dt out/img/kernel.elf

Disassembly of section .text:

00008000 <__start>:

# This triple dot (...) signifies that everything are zeroes.

...

00010000 <_start>:

# The first instruction

10000: ee105fb0 mrc 15, 0, r5, cr0, cr0, {5}

10004: e2055003 and r5, r5, #3

10008: e3550000 cmp r5, #0

1000c: 1a00000d bne 10048 <halt>

10010: e59f5038 ldr r5, [pc, #56] @ 10050 <halt+0x8>

10014: e1a0d005 mov sp, r5

10018: e59f4034 ldr r4, [pc, #52] @ 10054 <halt+0xc>

1001c: e59f9034 ldr r9, [pc, #52] @ 10058 <halt+0x10>

10020: e3a05000 mov r5, #0

10024: e3a06000 mov r6, #0

10028: e3a07000 mov r7, #0

1002c: e3a08000 mov r8, #0

10030: ea000000 b 10038 <_start+0x38>

10034: e8a401e0 stmia r4!, {r5, r6, r7, r8}

10038: e1540009 cmp r4, r9

1003c: 3afffffc bcc 10034 <_start+0x34>

# This is where we jump to kernel_main

10040: e59f3014 ldr r3, [pc, #20] @ 1005c <halt+0x14>

10044: e12fff33 blx r3

00010048 <halt>:

10048: e320f002 wfe

1004c: eafffffd b 10048 <halt>

10050: 00010000 .word 0x00010000

10054: 00013000 .word 0x00013000

10058: 00014000 .word 0x00014000

# This contains the address of kernel_main symbol.

# Note the @ hint in instruction address 0x10040.

1005c: 000102c0 .word 0x000102c0

...

# Our kernel C code entry point.

000102c0 <kernel_main>:

102c0: e3a00002 mov r0, #2

102c4: e92d4010 push {r4, lr}

102c8: ebffff64 bl 10060 <uart_init>

102cc: e59f0010 ldr r0, [pc, #16] @ 102e4 <kernel_main+0x24>

102d0: e08f0000 add r0, pc, r0

102d4: ebffffef bl 10298 <uart_puts>

102d8: ebffffdf bl 1025c <uart_getc>

102dc: ebffffd0 bl 10224 <uart_putc>

102e0: eafffffc b 102d8 <kernel_main+0x18>

102e4: 00000d28 .word 0x00000d28

Note that the instruction mrc 15, 0, r5, cr0, cr0, {5} matches with what we had on boot.S file. I am going to take note of the hex representation of this memory value: ee105fb0 (this is in little-endian notation).

Let’s confirm on QEMU whether the instructions are located in 0x10000 or not.

1

2

3

4

(qemu) xp/12w 0x10000

0000000000010000: 0xee105fb0 0xe2055003 0xe3550000 0x1a00000d

0000000000010010: 0xe59f5038 0xe1a0d005 0xe59f4034 0xe59f9034

0000000000010020: 0xe3a05000 0xe3a06000 0xe3a07000 0xe3a08000

So it lives there! But why not 0x8000? One thing, is that the section __start starts at 0x8000, but all were zeroes until it reaches section _start at 0x10000 (basically an amount of 0x8000 bytes of zeroes).

Here we find out that our kernel binary has a padding starting from address

0x8000until0x10000. This is actually an issue, but we still boot correctly for some reason. For now, let’s accept this and discuss about this issue on a later section.

What if we check out the QEMU instance using kernel7.img?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

> qemu-system-arm \

-nographic \

-M raspi2b \

-kernel out/img/kernel7.img

QEMU 9.0.2 monitor - type 'help' for more information

(qemu) xp/40w 0x8000

0000000000008000: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008010: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008020: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008030: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008040: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008050: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008060: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008070: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008080: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000008090: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

(qemu) xp/40w 0x10000

0000000000010000: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010010: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010020: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010030: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010040: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010050: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010060: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010070: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010080: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0000000000010090: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

There are basically none! What happened? I dumped the guest’s physical memory, then manually searched for the first instruction.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

> qemu-system-arm \

-nographic \

-M raspi2b \

-kernel out/img/kernel7.img

QEMU 9.0.2 monitor - type 'help' for more information

(qemu) dump-guest-memory guestdump.bin

(qemu) quit

# Note here that I am looking for "b05f 10ee",

# which is actually ee105fb0 written as little endian memory.

> xxd guestdump.bin | grep -A10 "b05f 10ee"

00018ae0: 0000 0000 b05f 10ee 0350 05e2 0000 55e3 ....._...P....U.

00018af0: 0d00 001a 3850 9fe5 05d0 a0e1 3440 9fe5 ....8P......4@..

00018b00: 3490 9fe5 0050 a0e3 0060 a0e3 0070 a0e3 4....P...`...p..

00018b10: 0080 a0e3 0000 00ea e001 a4e8 0900 54e1 ..............T.

00018b20: fcff ff3a 1430 9fe5 33ff 2fe1 02f0 20e3 ...:.0..3./... .

00018b30: fdff ffea 0000 0100 0030 0100 0040 0100 .........0...@..

00018b40: c002 0100 f04f 2de9 4491 9fe5 0300 50e3 .....O-.D.....P.

00018b50: 0990 8fe0 0b00 00ca 0100 50e3 4200 00da ..........P.B...

00018b60: 3f34 a0e3 2c61 9fe5 2c51 9fe5 2c41 9fe5 ?4..,a..,Q..,A..

00018b70: 2ce1 9fe5 2cc1 9fe5 2c81 9fe5 2c71 9fe5 ,...,...,...,q..

00018b80: 2ca1 9fe5 0a00 00ea 0400 50e3 3600 001a ,.........P.6...

The memory dump shows it is located at around 0x18000, which is way off! How did I get 0x18000? Actually the guest memory dump has an ELF metadata at the top, so the memory starting point has a bit of offset there. I quickly verified this by peeking the guest’s memory:

1

2

3

4

5

(qemu) xp/12w 0x18000

0000000000018000: 0xee105fb0 0xe2055003 0xe3550000 0x1a00000d

0000000000018010: 0xe59f5038 0xe1a0d005 0xe59f4034 0xe59f9034

0000000000018020: 0xe3a05000 0xe3a06000 0xe3a07000 0xe3a08000

Now we should know it won’t work! Based on the behavior, we may conclude that QEMU mounted the kernel7.img on 0x10000 (because we have a 0x8000 bytes of padding from _start). In order to make our machine boot correctly, the kernel7.img must be mounted right on 0x8000.

Why? Remember our binary analysis of the ELF file. objcopy will just strip those ELF metadata, remove the padding from 0x0000 - 0x8000, while leaving the binary structure intact.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

> arm-none-eabi-objdump -dt out/img/kernel.elf

Disassembly of section .text:

00008000 <__start>:

# This triple dot (...) signifies that everything are zeroes.

...

00010000 <_start>:

# The first instruction

10000: ee105fb0 mrc 15, 0, r5, cr0, cr0, {5}

10004: e2055003 and r5, r5, #3

# <... cut for clarity>

# This is where we jump to kernel_main

10040: e59f3014 ldr r3, [pc, #20] @ 1005c <halt+0x14>

10044: e12fff33 blx r3

00010048 <halt>:

# <... cut for clarity>

# This contains the address of kernel_main symbol.

# Note the @ hint in instruction address 0x10040.

1005c: 000102c0 .word 0x000102c0

...

# Our kernel C code entry point.

000102c0 <kernel_main>:

# <... cut for clarity>

- Checking out instruction address

0x10040from the ELF, it reads the address0x1005cwhich contains the address tokernel_main, then jump to that address. - This value inside

0x1005ci.e.0x00102c0, is already hardcoded during linking process. - Therefore, our program already has an assumption that it will run starting from

0x8000. This assumption comes from the line. = 0x8000in the linker script. - If the program did not mount correctly on

0x8000, then the jump destination will be wrong.

Without any regards of where did the program counter went, we already proven that our binary will not work correctly. Now, how do we fix this?

A quick Google search points me to a StackOverflow question asking an interestingly similar issue: Qemu doesn’t load my Image file at my specified address. Apparently, using -kernel option means to follow the Linux’s procedure of mounting the kernel image. I don’t know how it went well if we use the ELF file, perhaps it had an extra logic when using it…

They said that the correct way to do it is to use the generic loader instead of -kernel i.e.

1

-device loader,file=out/img/kernel7.img,addr=0x8000,cpu-num=0

So let’s try that!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

> qemu-system-arm \

-nographic \

-M raspi2b \

-device loader,file=out/img/kernel7.img,addr=0x8000,cpu-num=0

Hello, kernel World!

QEMU 9.0.2 monitor - type 'help' for more information

(qemu) x/40w 0x8000

00008000: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008010: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008020: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008030: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008040: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008050: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008060: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008070: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008080: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

00008090: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

(qemu) x/40w 0x10000

00010000: 0xee105fb0 0xe2055003 0xe3550000 0x1a00000d

00010010: 0xe59f5038 0xe1a0d005 0xe59f4034 0xe59f9034

00010020: 0xe3a05000 0xe3a06000 0xe3a07000 0xe3a08000

00010030: 0xea000000 0xe8a401e0 0xe1540009 0x3afffffc

00010040: 0xe59f3014 0xe12fff33 0xe320f002 0xeafffffd

00010050: 0x00010000 0x00013000 0x00014000 0x000102c0

00010060: 0xe92d4ff0 0xe59f9144 0xe3500003 0xe08f9009

00010070: 0xca00000b 0xe3500001 0xda000042 0xe3a0343f

00010080: 0xe59f612c 0xe59f512c 0xe59f412c 0xe59fe12c

00010090: 0xe59fc12c 0xe59f812c 0xe59f712c 0xe59fa12c

Yay, now it worked! The memory structure also shows the same contents as using the ELF file.

‘Extra’ paddings

What’s going on with those null bytes at 0x8000?

In the raw binary, we can see these null bytes, too, until we reach 0x8000:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

> xxd -l 80 -s 0x0000 out/img/kernel7.img

00000000: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000010: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000020: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000030: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000040: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

> xxd -l 80 -s 0x7FD0 out/img/kernel7.img

00007fd0: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00007fe0: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00007ff0: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00008000: b05f 10ee 0350 05e2 0000 55e3 0d00 001a ._...P....U.....

00008010: 3850 9fe5 05d0 a0e1 3440 9fe5 3490 9fe5 8P......4@..4...

In ELF structure, we see this padding from 0x8000 to 0x10000. Where is it coming from?

There were two places where we “move” the program line counter:

- Assembly file

boot.S, specifically at line where we do.org 0x8000.orgdirective means origin. It sets the location of the next instruction (or current section, if it placed after a section) to the specified address.

- Linker script

linker.ld, specifically at. = 0x8000.- This moves the program line counter to

0x8000.

- This moves the program line counter to

So what happened was section .text.boot from boot.o produces a padding because of .org directive.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

> arm-none-eabi-objdump -d out/obj/boot.o

out/obj/boot.o: file format elf32-littlearm

Disassembly of section .text.boot:

00000000 <_start-0x8000>:

# null padding here

...

00008000 <_start>:

8000: ee105fb0 mrc 15, 0, r5, cr0, cr0, {5}

# <... cut for clarity>

This causes the linker to also include that padding from .text.boot when including that data, as explicitly described on KEEP(*(.text.boot)), on top of another padding from . = 0x8000. Note that 0x8000 + 0x8000 = 0x10000.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

> arm-none-eabi-objdump -d out/img/kernel.elf

out/img/kernel.elf: file format elf32-littlearm

Disassembly of section .text:

# 0x0000 - 0x8000 padding is from linker script

00008000 <__start>:

# This padding is from .text.boot (boot.o)

...

00010000 <_start>:

10000: ee105fb0 mrc 15, 0, r5, cr0, cr0, {5}

10004: e2055003 and r5, r5, #3

10008: e3550000 cmp r5, #0

# <... cut for clarity>

To solve this, we should remove .org 0x8000 directive from the boot.S. After removing the line and rebuilding, it all looks good now:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

> arm-none-eabi-objdump -dt out/img/kernel.elf

out/img/kernel.elf: file format elf32-littlearm

Disassembly of section .text:

00008000 <__start>:

# No more extra 0x8000 null paddings here!

# __start and _start now point at the same place.

8000: ee105fb0 mrc 15, 0, r5, cr0, cr0, {5}

8004: e2055003 and r5, r5, #3

8008: e3550000 cmp r5, #0

800c: 1a00000d bne 8048 <halt>

# <... cut for clarity>

> xxd -l 80 -s 0x0000 out/img/kernel7.img

# Now the first byte points to the correct instruction!

# No more null bytes!

00000000: b05f 10ee 0350 05e2 0000 55e3 0d00 001a ._...P....U.....

00000010: 3850 9fe5 05d0 a0e1 3440 9fe5 3490 9fe5 8P......4@..4...

00000020: 0050 a0e3 0060 a0e3 0070 a0e3 0080 a0e3 .P...`...p......

00000030: 0000 00ea e001 a4e8 0900 54e1 fcff ff3a ..........T....:

00000040: 1430 9fe5 33ff 2fe1 02f0 20e3 fdff ffea .0..3./... .....

I had a quick look on Google on the interactions between

.orgdirective and linker’s location counter setting [1] [2] they seem to imply that, if possible, we should only use one of them (if we use linker, don’t use.org.). Perhaps from now on we should use linker’s location counter settings only.

We were lucky

We were actually very lucky because those null bytes 0x00000000 actually means NOP on ARM 32 bit instruction. On ARM 64 bit instruction it was different: udf #0 which I learned that it means an “undefined” instruction, and it could trap the processor to do some exception handlings, but I don’t know the exact behavior on QEMU.

This means that once the program counter reaches 0x8000, it ran multiple NOPs until it reached 0x10000. This was the case when running the raw binary image, but I’m not sure about the ELF image because it had an entry point metadata and could’ve skipped right to 0x10000.

Conclusion

We had a lot of lessons learned here by creating a bare metal “Hello world” program for Raspberry Pi under QEMU. We observed how a linker produces the binary, how to read the objdump outputs, and how to make QEMU load our binary on the right place.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t test my binary because I don’t have the real device on my hand.

Next steps

Perhaps, we can retry our experiment using a newer devices supported by QEMU like Raspberry Pi 4. I can also try to extend our functionality of the program, and make it a functional OS someday?

Should I buy a Raspberry Pi just for this?